The copy of Robert Steele, the editor of Bacon's Opera Hactentus

Perspectiva. . . Nunc primum in lucem edita opera. . . lohannis Combachii.

Frankfurt: Wolfgang Richter for Anton Humm, 1614.

1st Edition. Hardcover. Very Good. Item #002782

4to (205 x 163 mm). [8], 189 (i.e. 207) [1] pp., 4 plates, numerous woodcut diagrams and woodcut ornaments in text. Signatures: ):(4 a-cc4. 18th century vellum covered boards, new endpapers, original flyleaves bound in (binding restored, vellum extensively soiled and marked). Leaves partially uncut. Text browned throughout, occasional foxing and spotting, title soiled and with small hole not affecting text, occasional dust soiling to outer page margins, small holes in margin of leaf 2c1 repaired, ink scribbling on front flyleaf, contemporary ink note on lower flyleaf, some pencil notes in text. Provenance: Robert Steele* (ink ownership stamp at tail of title); Birkbeck College (blind stamps to title-page and leaf 2b4). A handsome copy. ----

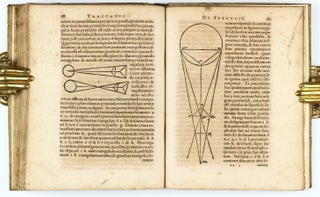

Becker 27; Hoover 73; DSB I, p. 377-84. - FIRST EDITION, edited from the manuscript by Johann Crombach (1585-1651). Bacon's main sources for his theories on optics and perspective were Euclid, Ptolemy, and Alhazen, and he 'followed Grosseteste in emphasizings the use of lenses, not only for burning, but also for magnification, to aid natural vision' (DSB).

*Robert Steele (1860-1944) was a British scholar and medievalist, best known for editing the 16-volume Opera hactenus inedita Rogeri Bacon. His publications of Bacon's works attracted funding from several learned societies, as well as a Civil List Pension and an Honorary Doctorate from Durham University. He was also one of the early Executive Members of the International Academy of the History of Science. His house and personal library were destroyed in a German air raid in 1941. (Wikisource).

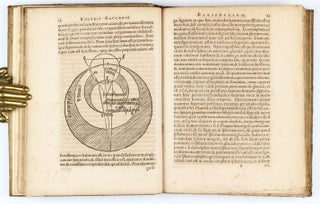

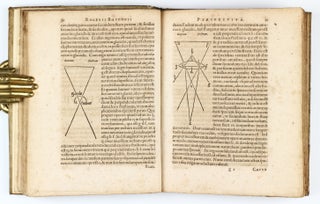

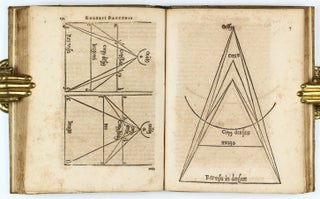

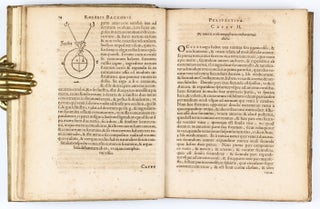

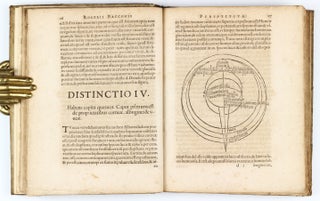

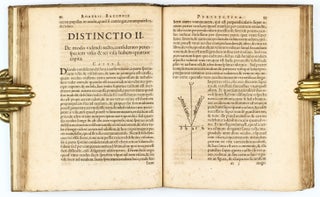

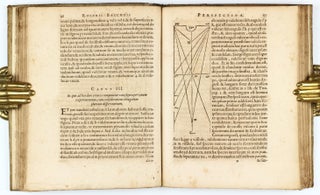

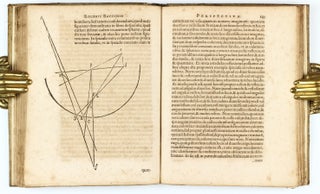

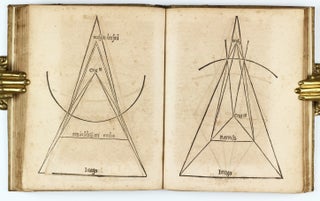

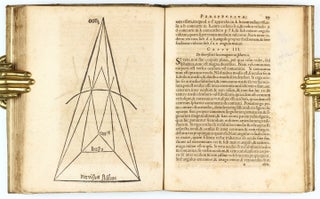

The highly developed knowledge of Greek antiquity in the matter of light, vision, and colour was unknown in its raw form to the Middle Ages, although Pliny's Historia naturalis, of which book XI is extensively concerned with the eye, was known and excerpted. Oddly enough, Pliny was not known to Isidore of Seville, who does in his Etymologiae, the great encycolopaedia of the period, discuss optical matters and the eye. Earlier, St. Augustine had in various passages, and notably in his commentary on Genesis, expounded the doctrine of the 'extramissionists', i.e. those who held that sight is the extramission from the eye of the person seeing of a 'fire'. This idea was enlarged upon, taking ideas from Plato's Timaeus and the commentary of Chalcidius on it (known through the Middle Ages) by figures from around 1100 AD such as Adelard of Bath and William of Conches. According to these thinkers there is, as it were, a perpetual current or transmission between the eye of the observer and the object observed: the effect of inflammation or disease of the eye on vision is cited as an indication of this. The Optica and Catoptrica of Euclid were translated into Latin (via the Arabic) about 1150 AD, as De visu or De aspectibus and De speculis. The De aspectibus is the work of Gerard of Cremona, and survives in three manuscripts. The first version of De visu was made from the Greek ('Ponatur ab oculo eductas rectas lineas ferri spatio...') and survives in a number of manuscripts, the earliest of the thirteenth centuty, although the whole matter is complicated by the fact that the same incipit may begin a text differing quite substantially in various ways. The De speculis ('Visum rectum esse cuius media terminos...') survives again in a large number of manuscripts, and there have been many printed editions, but not of the medieval translation. Gerard of Cremona translated from the Arabic the pseudo-Euclidian De speculis (Compositio speculorum mimbilium), beginning 'Preparatio speculi in quo videas alterius imaginem...', which circulated as Euclid's De speculis. In addition there were other works, notably the Latin translation by Eugene of Sicily from the Arabic version of Ptolemy's Optica or De aspectibus, a work known in some fourteen manuscripts. In addition there were works by the great Arab philosophers and commentators which touched in greater or lesser detail on the topic. The truly remarkable and important Englishman Robert Grosseteste (1168-1253), who knew Plato's Timaeus, and much more of the relevant literature, held that optical problems could be subjected to geometrical discussion and analysis, although he did not hold that everything could be resolved simply by geometry. It was Grosseteste who drew an elegant distinction (in his commentary on Aristotle's Analytica posteriora) between Propter quid and Quia demonstrations, the former causal and geometrical, and the latter using physical principles. The one important optical text unknown to Grosseteste was the work of Ibn al-Haytham. Albert the Great, teacher of Aquinas, probably did know his De aspectibus, just as he knew much other literature. Albert defended the autonomy of mathematics and physics, and refused to subordinate the latter to the former, although he did see that the science of Perspectiva, which was essentially geometrical, should be used to investigate the phenomenon of vision, and his view of vision was diametrically opposed to the school of the extramissionists. Roger Bacon, one of the 'founding fathers' of geometrical optics, was more or less a. contemporary of John Pecham, a Franciscan, whose Perspectiva communis circulated widely, although Bacon is today better known. He was utterly dismissive of the work of Albert the Great, and holds a position which is an extension of that of Grosseteste. In addition Bacon had a much better knowledge of the literature, in particular of Ptolemy and Ibn al-Haytham. His glorification of the importance of mathematics is powerful: 'there are four great sciences. . . and the gate and key of these sciences is mathematics. . . which has always been used by holy and wise men more than any other science. Its neglect. . . has ruined the whole educational system of the Latins. . . if one grasps the basic wisdom concerning this science and applies them correctly to knowledge of other sciences, one will be able to know all things. . . easily and powerfully' (Opus maius iv. 1.1.) Bacon clearly prefered Propter quid demonstrations, and his Perspectiva and De multiplicatione specierum are rich in geometrical argument and proof, copiously shown in geometrical illustrations (fifty-one such in the Perspectiva and thirty-nine in the De multiplicatione). Earlier sources had considered the problems of reflection and refraction of radiation, and Bacon fully understood the geometrical principles involved, and produced, for example, a highly sophisticated analysis of mirrors and mirror-images. Equally his treatment of refraction was skilled, although his geometry failed him when it came to discussing the anatomy of the eye, where Bacon argued following Ibn al-Haytham's De aspectibus but anatomical methods and findings were over-ridden by the demands of geometry. Similarly his geometrical explanation of how a circular image is achieved of a round object seen through a triangular or rectangular aperture is rigorous and beautifully demonstrated, but wrong, as Kepler was to show at the beginning of the seventeenth century. For Bacon, as for others, the central question of the Perspectiva was how we see, and it was in his De specierum multiplicatione that he discussed at length the nature of radiation: light and colour emanate in every direction from every point of the surface of a visible object and do this continuously; the path is represented by straight lines or rays; light is not a body but a likeness of the luminous body, what he calls corporeal form, a platonic form which in the case of light and colour takes on a material medium. He realised that seeing involved not only the eye but the brain also, and he divides the brain into 'cells' (following Avicenna), as well as giving a largely accurate account of the anatomy of the eye and the optic nerves. Following Ibn al-Haytham, Bacon gives a geometrical scheme which makes radiation enter the eye 'to yield a distincy and erect image' of what is the visual field. He believed that visual perception is engendered by radiation from the visual object to the eye (as Aristotle, Avicenna and ibn-al-Haytham) and that light and colour make a sort of impression on the 'crystalline humour' of the eye, and this impression of radiation on the eye he imagined as an infinite set of cones or pyramids, falling on the 'crystalline humour' in the same order as the points of origin in the visual field, and in a perpendicular way: oblique rays he explains as inherently weak; therefore only perpendicular rays produce vision, although all rays reaching the eye from a given point in the visual field may come together in the eye at a given point. Here we have the first glimmerings of the principle of focussing, which later became important. Bacon's attempt to reconcile the intromissionist theory with the extramissionist leads him to say that 'the eye must perform the act of sight of its own power' (he cites the weakness of the eye affecting sight), but at the same time he agrees with Aristotle's view that 'sense always receives the species of sensible things' and that it is this which constitutes the act of perception. In Part II of the Perspectiva Bacon recounts a whole range of optical phenomena - long sight, near sight, errors of vision, clarity of vision, on the moon, on our perceptions of magnitude, and so on, all drawing on a wide variety of earlier sources, and on experimentation. Part III deals with reflection and refraction, discussing the geometry of the former in various sorts of mirrors, showing a good understanding of focal point and focal plain. Ibn al-Haythgam when discussing the physics of reflection says 'light is moved very swiftly, and when it falls on a mirror it is not allowed to penetrate... since the original force and nature of motion still remain in it, the light is reflected in the direction from which it came'. Bacon took a different view: '[in the reflection of a species], the species undergoes no violence' but if resistance impedes its forwards motion, then the species 'generates itself in some other direction… for it could be violently driven back, as a ball from a wall, only if it were a body': there is nothing in the mirror, and when we see a rainbow, what we really see is a distortion of the sun outside its true place. Bacon treats of refraction similarly. Bacon sent his Opus maius, of which these treatises form part, to the papal court at Viterbo in 1267/68, and by the 1270s its influence was felt in the work of Witelo (d. 1281), a Silesian active there. Witelo followed much of what Bacon had argued. . . This 1614 edition, the first, is late: some ten years after Kepler's Paralipomena ad Vittelionem, which rewrote optics, and was published in Protestant Germany by Johann Combach, professor of philosophy, and later of theology, at Marburg, author of Metaphysicorum liber singularis. . . Combach was closely bound up with Rosicrucianism and this work has a preface addressed to the Rosicrucians (dropped from the second edition of 1620). It is dedicated to John Prideaux, Rector of Exeter College, Oxford, in the Bodleian library of which university Combach had studied in 1609 (and where he had found the Bacon manuscript he used for his edition). (David C. Lindberg: Roger Bacon and the origins of Perspectiva in the Middle Ages a critical edition. . . Introduction, Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1996; Sotheby's: Geometry and Spece, Sales Catalogue, 2002, 40).

A 4-leaf gathering containing diagrams, counted as [8] p. of plates is inserted between signatures t and u. Its first leaf bears a dagger-sign, but is outside the normal signature position.

Sold

Delivery time up to 10 days. For calculation of the latest delivery date, follow the link: Delivery times

Lieferzeit max. 10 Tage. Zur Berechnung des spätesten Liefertermins siehe hier: Lieferzeiten